Some of my beef jerky. Some of my beef jerky. This last summer, I (JF) made beef jerky for the first time. Not only is dried meat delicious, but it's fascinating because it's a way to preserve meat without requiring refrigeration. To me, that's absolute witch science: all my life I've been told that meat spoils quickly and, while food safety is important, there's a lot of wiggle room and interesting options for preserving meat without refrigeration. Here's the basics: Bacteria that spoil food are kind of like humans--they don't like it too hot, they don't like it too cold, they need air to breathe, something to feed on, and a little bit of water. If you want to inhibit the growth of these food-spoiling bacteria, you need to manipulate one or more of these variables and deprive them of what they need to live. Temperature is the most common: if you buy hamburger patties from the store, you'll refrigerate them to slow down bacterial growth, then throw it on the grill to kill any bacteria with heat. The magic of dehydration is that it deprives the bacteria of moisture, removing the urgent need to cook or chill the meat (so, more like bacteria famine than the bacteria ice age in the freezer or bacteria genocide on the grill). So, how to remove that moisture? The two most common tools are heat and air movement. The two combined are especially effective (which is why most food dehydrators have a fan). Although the USDA recommends heating beef to 160 degrees Fahrenheit to kill bacteria, it's more typical to dry it between 130 and 160 degrees (cooking a steak to 130-140 degrees F internal temperature is rare). Heat and air movement are such simple ingredients that you'll soon realize you may not need a "real" food dehydrator: you can dry out meet in an oven, over a fire, in a solar cooker, or just out in the sun. Or maybe, in a car on a hot day… There are still food safety risks even after drying. Remember, drying doesn't kill bacteria, it only inhibits their growth. There may still be dangerous bacteria on the meat before or after drying, and the growth of that bacteria will accelerate if you leave your dried jerky in a warm, moist, or oxygen-rich environment. Remember, the danger zone for food spoilage is 40-140 degrees Fahrenheit. So, it also goes without saying that any meat drying or processing is a thing you do at your own risk. To me, though, that's one of the coolest things about making beef jerky: You take responsibility into your own hands. Can you do that badly? Of course. But to me it's definitely worth it--especially because beef jerky is so delicious. Plus, it makes you a master of beef jerky witch science.

2 Comments

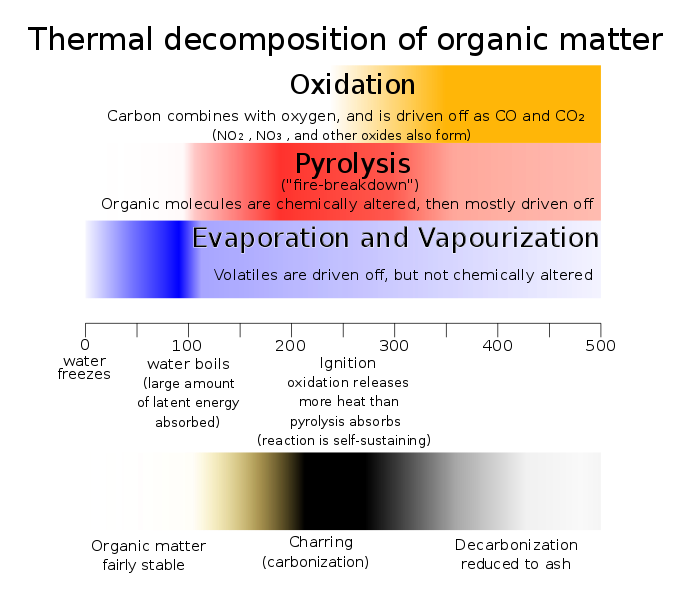

Charcoal is a substance that we use a lot of on our channel, and we're not alone. You've probably used it for a barbecue and lump charcoal used to be the fuel of choice for industrial processes before the advent of coal and coke. So what is charcoal and how is it made? Chemically speaking, charcoal is almost pure carbon. It's made from wood by driving off everything in the wood that isn't carbon, e.g., water, tar, and volatile gases. This process, induced by heat between 600-1100 degrees Fahrenheit, is called pyrolysis. The product is charcoal. It's worth noting that the pillow-shaped briquettes you buy in a grocery store are not pure carbon; they have a binder and other additives (hence why they leave so much ash behind after burning; good quality charcoal should barely leave any ash at all when burnt). So how do you make it? Again, pyrolysis happens around 600-1100 degrees Fahrenheit. Obviously this occurs partially whenever a wood fire is lit, so you can make charcoal just by lighting a wood fire and collecting the charcoal that is left afterwards (what's called the "direct" method). However, it also isn't terribly efficient since large quantities of charcoal are made and then burned in the same fire. Another option is the "indirect" method: seal wood into a nearly airtight container and bake it inside a second fire (you may have made charcloth in a similar way using a small metal tin and your kitchen oven). This leaves all the wood in the sealed chamber as charcoal (minus the volume of water, tar, and gases). However, it requires a secondary fire, so although it yields a cleaner "harvest" of charcoal, it still seems to lack some desired efficiency. Whether you use the direct or retort method, your charcoal making venture basically comes down to two variables: 1) heat creation/retention and 2) oxygen. Unless you cut the oxygen flow to the fire down to nothing or near nothing, the wood will pyrolyze into charcoal and then combust and burn away (i.e., what happens in a normal fire). And whatever you do, there has to be some kind of heat source to raise the temperature of the wood between 600-1100 degrees Fahrenheit and then keep it there for a long enough period of time to complete pyrolysis. How you accomplish those two tasks is up to you, but they both have to occur. On the channel, we've used an old barbecue and a 55-gallon drum as ovens and retorts for the direct and indirect methods respectively. The 55-gallon drum we use has a steel pipe flue welded onto it that in theory should allow the volatile gases to exit the retort then combust and contribute more heat to the retort, but we've had mixed results with the flue. Even a simple earth chamber, above or below ground, can provide the insulation to retain heat as well as cut off oxygen flow. Remember the two golden rules: Heat/insulation and oxygen flow. Go and may the charcoal be with you. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed